Thumbnail-Configuration

Please select a thumbnail configuration.

Super Resolution Microscopy

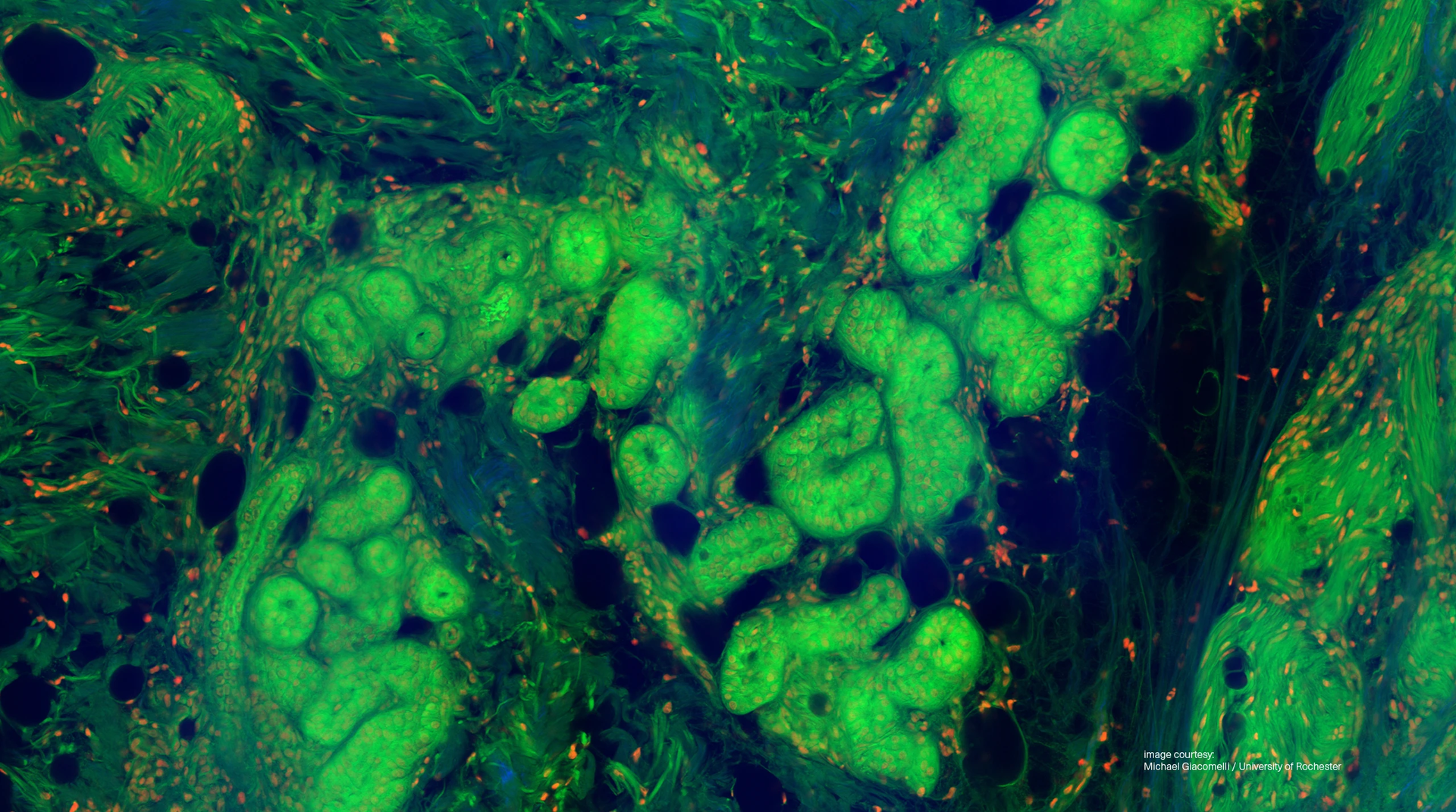

Beyond the diffraction limit – Seeing life at the molecular scale

For over a century, the diffraction limit of light has defined how finely we could see into the living world — about 200 nanometers in the lateral plane and 500 nanometers in depth.

Today, super-resolution microscopy has broken that barrier.

Techniques such as STED, SIM, PALM, and STORM have pushed optical imaging into the nanoscale domain, revealing details once thought to be accessible only by electron microscopy — but in living, dynamic, and functional biological systems.

Behind every super-resolution technique lies one common enabler: precisely engineered laser light — coherent, stable, and tunable across multiple wavelengths.

Lasers are the sculptors of the light field, enabling researchers to illuminate biological structures smaller than the wavelength of light itself.

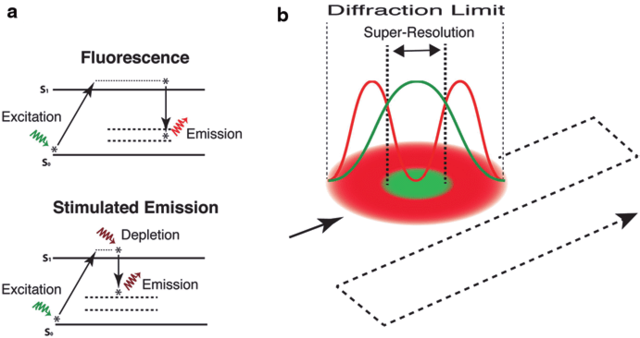

The principle: Beating diffraction with light and clever physics

Traditional fluorescence microscopy is limited by the wave nature of light — structures closer than ~200 nm blur together.

Super-resolution microscopy circumvents this by using nonlinear optical processes, structured illumination, or single-molecule localization to sharpen or reconstruct the image far beyond the diffraction limit.

Each technique achieves this in a different way:

STED (Stimulated Emission Depletion Microscopy)

STED uses two synchronized laser beams:

- an excitation beam to turn fluorophores on, and

- a donut-shaped depletion beam to switch them off everywhere except at the very center.

The result is a sub-diffraction excitation spot, shrinking the effective fluorescence area down to 20–30 nm resolution.

The smaller the depletion beam’s effective radius — the higher the resolution.

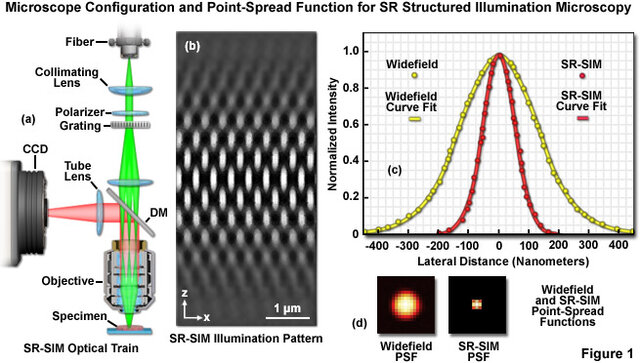

SIM (Structured Illumination Microscopy)

SIM illuminates the sample with interfering light patterns (gratings) and analyzes the resulting Moiré fringes to reconstruct high-resolution images.

This doubles the resolution of conventional microscopy, achieving ~100 nm in lateral resolution — ideal for live-cell imaging, as it uses moderate light intensities and standard fluorophores.

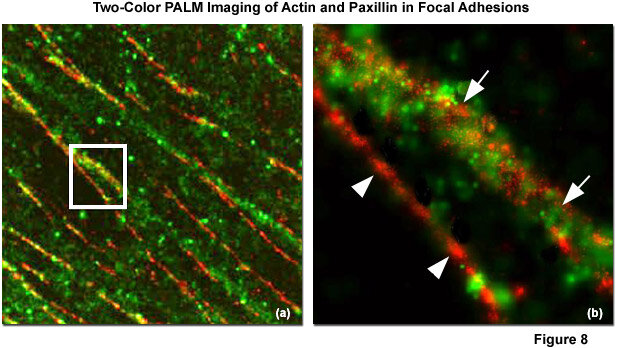

PALM & STORM (Photo-Activated Localization/ Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy)

PALM and STORM use photo-switchable fluorescent molecules, but only activate a sparse subset of them at a time.

By localizing the center of each emission spot with nanometer precision and reconstructing thousands of frames, they produce images with 10–30 nm resolution — revealing molecular arrangements and interactions with exquisite detail.

Why super-resolution microscopy matters

Super-resolution microscopy is one of the most transformative advances in modern biophotonics.

It allows researchers to observe the molecular machinery of life directly — from protein complexes and synapses to chromatin structure and membrane organization.

These technologies have enabled breakthroughs in:

- Neuroscience: mapping synaptic architecture and neurotransmitter dynamics.

- Cell biology: visualizing cytoskeletal filaments and organelle contacts.

- Virology: revealing viral entry and replication at the nanoscale.

- Cancer research: studying protein clustering and receptor signaling.

By combining spatial resolution, live-cell compatibility, and molecular specificity, super-resolution microscopy provides a bridge between biochemistry and cell physiology.

Typical biological samples

Super-resolution microscopy is used across diverse biological systems, including:

- Neuronal networks (synaptic vesicles, actin filaments, dendritic spines)

- Membrane receptor clusters and protein assemblies

- Chromatin structure and transcription foci in cell nuclei

- Microtubules, mitochondria, and Golgi networks

- Viral particles and immune synapses

Fluorescent proteins (e.g., GFP, mCherry) and dyes (e.g., Alexa Fluor, Atto, or Cy dyes) are chosen for stability and switching behavior — and their excitation wavelengths define the laser requirements.

The role of lasers in super-resolution microscopy

Lasers are the beating heart of every super-resolution microscope.

They provide the monochromatic, coherent, and temporally controlled illumination necessary for precise excitation, depletion, and photoactivation.

To achieve nanometer-scale resolution, lasers must deliver:

- Multiple stable wavelengths covering 405–785 nm for various fluorophores.

- Excellent beam quality (TEM₀₀) for uniform, diffraction-limited focusing.

- Low noise and power stability to prevent signal fluctuations during long acquisitions.

- Fast modulation for synchronization in time-gated or pulsed excitation modes.

- High power for depletion (STED) and switching (PALM/STORM) beams.

Laser requirements for each super-resolution technique

| Technique | Typical lasers / wavelengths | Pulse / power requirements | Key laser features |

|---|---|---|---|

| STED | Excitation: 488, 561, 640 nm; Depletion: 592, 775 nm | High-power CW or pulsed depletion (~100 mW–1 W) | Excellent beam shaping, low timing jitter, stable polarization |

| SIM | 405–640 nm (multi-wavelength excitation) | Moderate power CW or modulated beams | High coherence, low intensity noise, fast modulation (<µs) |

| PALM / STORM | 405 nm (activation), 488/561/640 nm (excitation) | CW or modulated beams (10–100 mW) | Low noise, stable long-term output, precise modulation control |

| Two-color PALM / STORM |

Dual lasers, typically 561 nm & 640 nm | Independent control, high stability | Perfect wavelength matching and cross-talk suppression |

Advantages vs. conventional confocal microscopy

| Parameter | Confocal microscopy | Super-resolution microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | ~200 nm lateral, ~500 nm axial | 20–100 nm (STED, PALM/STORM), 100 nm (SIM) |

| Photobleaching | Moderate to high | Lower for SIM; higher for STED/PALM if not optimized |

| Sample types | Fixed or live | Live-cell compatible (SIM, fast STED) |

| Complexity | Simple optical design | Requires precise laser control & synchronization |

| Information | Organelles & structures | Molecular-scale localization and dynamics |

In short:

Super-resolution microscopy extends the range of light microscopy from the cellular to the molecular scale — enabling researchers to see how life works, one molecule at a time.

Challenges and drawbacks

Each method offers unique strengths — and trade-offs:

- STED: Highest spatial resolution (~20 nm), but requires high depletion power and photostable dyes.

- SIM: Gentle, fast, and live-cell friendly, but limited to ~100 nm resolution and complex reconstruction algorithms.

- PALM/STORM: Ultimate single-molecule accuracy (10–20 nm), but acquisition is slow and relies on fluorophore blinking behavior.

Researchers often combine methods — such as SIM for dynamics and STED for fine details — leveraging laser flexibility for hybrid imaging systems.

Latest laser advances: Multi-wavelength fiber-coupled systems

Modern multi-laser engines now deliver violet to near-infrared wavelengths (405–785 nm) through a single fiber-coupled output.

Features like COOL AC active temperature control ensure long-term power and pointing stability, while direct diode modulation enables nanosecond switching between lines — critical for time-gated or fast-scanning setups.

These compact laser systems drastically simplify microscope integration and minimize alignment drift, making turnkey, multi-color super-resolution imaging accessible for both research and core facilities.

Scientific breakthroughs powered by super-resolution microscopy

Super-resolution microscopy has fundamentally transformed biological imaging.

- Revealing the cytoskeleton at nanometer scale:

Using STED, researchers visualized actin and microtubule organization in living cells at 20 nm precision (Hell et al., Nature, 2000). - Mapping protein localization in synapses:

PALM imaging uncovered how neurotransmitter receptors cluster in the neuronal membrane (Betzig et al., Science, 2006). - Chromatin architecture and gene expression:

STORM revealed how active and inactive DNA regions organize within the nucleus, offering insights into transcriptional control. - Viral infection pathways:

SIM and STORM visualized how viruses enter and uncoat within host cells, revealing targets for antiviral strategies.

Light that breaks barriers

Super-resolution microscopy represents the culmination of decades of innovation in optics and laser technology.

By combining multiple stabilized wavelengths, high beam quality, and ultra-low noise, TOPTICA’s laser solutions empower researchers to transcend the diffraction limit and explore biology at the nanometer scale.

TOPTICA Photonics:

Delivering the light that reveals life beyond its limits — one molecule at a time.